0 Before the First Proof

0.1 Introduction to the Class

Objectives:

-

•

Motivate the study of logic as a gateway to mathematical discovery

-

•

Briefly glimpse into our future trajectory as we embark on our journey

0.1.1 There’s Something to Logic

Let’s consider the following logic puzzle (thanks to PuzzleBaron for hosting these!):

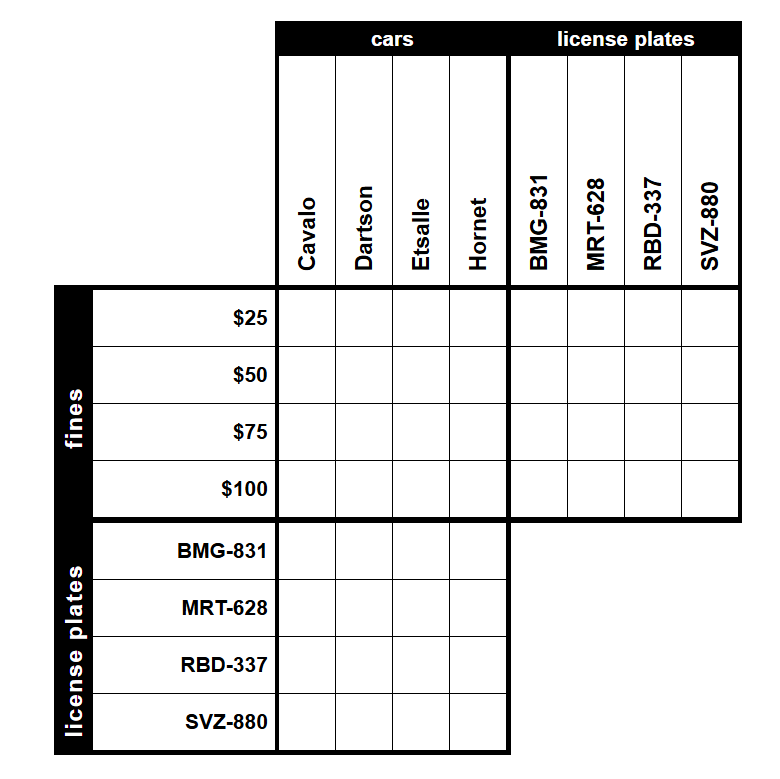

Sal, a newly-hired police offer, has written a number of parking violations this week. She receives an angry email from one of the violators asking why they received a $100 fine. Unfortunately, Sal’s paperwork is all distraught, and she only has some distinct memories of each of the tickets she wrote. Help her sort out her paperwork and find out which car received the $100 fine. (No option in any category will ever be used more than once.)

-

1.

The automobile that received the $75 fine has the BMG-831 plates.

-

2.

The four cars are the car with the SVZ-880 plates, the automobile that received the $100 fine, the Dartson and the Etsalle.

-

3.

The Etsalle was fined $50.

-

4.

The Cavalo is either the automobile with the RBD-337 plates or the automobile that received the $50 fine.

As a child I remember solving logic puzzles like this in my spare time, but perhaps this is your first time seeing something like this. The goal of these puzzles is to train your brain to follow logical trains of thought and make deductions that aren’t explictly told to you.

For example, since there are four cars in this problem, item 2 tells us that the Dartson and Etsalle don’t have SVZ-880 plates, and they weren’t the ones that received the $100 fine. Referencing item 4, the Cavalo had to be the one with the RBD-337 plate as item 3 says that Etsalle was the one that was fined $50. Hence combining this with what we know from item 2 again, the Hornet had to be the car with the SVZ-880 plate, and the Cavalo was the one that received the $100 fine.

0.1.2 Training in Logic

Oh my goodness, I forgot you all were there! Did you follow what I was saying? Some of you did (ha! likely story), and some of you didn’t. Even if you have been studying mathematics for a while now, you may not have received formal training in mathematical logic. Up to now it’s largely because the need for you to be trained in logic was minimal, as we instructors have been communicating the logic that other mathematicians have been giving you. But… and let me be frankly honest with you here… we need you to know logic in order to keep advancing your mathematics career.

When I say I’m a mathematician to the person on the plane next to me, they are surprised to hear I am researching mathematics. While they don’t vocalize it exactly like this, the reasoning is always about the same: “Isn’t math basically done after calculus and linear algebra?”

But any actuary will tell you that is wrong. They use an enormous amount of mathematical data science in their job which uses a humongous amount of approximation theory, a subject that relies on discoveries in applied and theoretical analysis. Any teacher will tell you they are wrong, because more and more they are discovering that their students are needing to learn subjects like graph theory and data science in order to open up their students’ future vocations in mathematics. Anyone who has opened up the arXiv will be floored at how many papers of new mathematics are being posted by mathematicians around the world every single day. In order to prepare you for the next stage of your mathematical career, we must train you in logic. This is a gateway course into nearly every mathematics class you will take beyond this point.

0.1.3 Training in Logical Communication

Even if you have received training in logic, you may not have received training in communicating logically. That’s the mistake I made in the logic puzzle: while I was explaining the logic that was going on in my head, I could have explained it better. I should have organized my thoughts more clearly so that I could tell you what I was thinking… but how do I do that?

Well, for one thing, I could have given a deeper explanation for my logical conclusions. Why is the Cavalo the one that received the $100 fine? I’m going to take a deep breath and explain my reasoning below:

-

•

We know from the problem that there are four cars: the Cavalo, the Dartson, the Etsalle, and the Hornet. Item 2 lists two of those cars - the Dartson and the Etsalle - but then says that the other two cars are those with the SVZ-880 plate and the $100 fine. I know the cars must be all different in this list because there are four cars and four descriptions, so they must match one-to-one.

-

•

So which one is the Cavalo: the one with the SVZ-880 plate or the one with the $100 fine? Well, we get a hint from item 4: we know the Cavalo either received the $50 fine or has the RBD-337 plate.

-

•

But item 3 says that the Etsalle received the $50 fine. Since no fine amount could be used more than once, that means the Cavalo didn’t receive the $50 fine.

-

•

So returning to item 4, the Cavalo must have had the RBD-337 license plate.

-

•

Returning to item 2 now: the Cavalo cannot have had the SVZ-880 plate as we just found out it has the RBD-337 license plate. Therefore, the Cavalo is the car that received the $100 fine.

Notice how much easier it is to follow this train of thought. It may take a few times to read through these items, but hopefully you are now convinced that my reasoning is correct! When I am convincing others that my reasoning is true, I have to take great care in how I communicate to others.

Now someone might raise a question: “But John, I understood your first explanation, and I didn’t need the second explanation to understand!” Good! The more you review logical arguments, the more these concise arguments will suffice for understanding even complex ideas. In this course we will learn how to eventually make our arguments concise as well, but first I want to make sure we understand everything that we are writing down by going one step at a time.

0.1.4 Proofs and Refutations

In 1976 Irme Lakatos wrote a book called Proofs and Refutations: The Logic of Mathematical Discovery. In the book a group of students have dialogue about a concept called the Euler characteristic, which is presented as a conjecture: “for all polyhedra , where is the number of vertices, the number of edges, and the number of faces.” I have included a tract from Lakatos’s text in this link so you can read some of this conversation.

It may surprise you that the conversation about something quite well known in mathematical circles very quickly goes off the rails. For something as well-discussed as this Euler characteristic, it is very hard to prove it to be true for all polyhedra. In the text, the teacher presents a “proof” by showing it to be true specifically for cubes, but the students begin to pose several counterarguments. To summarize the students’ questions:

-

1.

What counts as a polyhedron? This is a dispute of definition. This is important, as a sphere has 1 face, no vertices, and no edges, so it does not satisfy the Euler characteristic.

-

2.

Given we have defined polyhedra, why does showing a proof of the fact works for a cube mean that it works for all polyhedra? The teacher’s proof is known as a “proof” by example, and it doesn’t work well in mathematics, as there could very well be examples that show the opposite of what we wish to prove.

Some of you may balk at this criticism as being pedantic, because certainly the Euler characteristic has to be true. Why else would we talk about it? But our question boils down to one from the beginning when this formula was first discovered: how do we know that the Euler characteristic is true?

If I am building a car, I must have full faith that the pieces I’m using to build it are sturdy in and of themselves, will withstand all reasonable weather conditions, and will work together no matter what stress I put them under. Otherwise we might find our car breaking while driving down the highway. And we can’t build a car without mathematics… we can’t build much of anything these days without mathematics… so our mathematics must be the most sturdy structure of them all.

0.1.5 Proofs and Their Structure

So in this course you will see things follow this pattern: “definition”, “theorem”, and “proof”. We will write our definitions very carefully so that what we say is exactly what we mean. Our very first definition will say the following:

Definition 0.1.1.

An integer is even if for some integer .

So 2 is an even number because . The number 3 is not even because it cannot be written as 2 times an integer. But this definition also means that is even. It also means that is even. This is not the typical definition that we get for an even number before this point, but what would that definition have been anyway? These may have been “definitions by example” (an even number is a number like 2, 4, 6, 8…), which obviously won’t work for us very well! Plus, many things that we like about even numbers work with this definition:

Theorem 0.1.2.

The sum of two even numbers is itself even.

How do we prove this? Here are some examples of proofs that will not work:

“Proof” by Example.

The sum equal 4. The sum equals 8. The sum equals 8.∎

“Proof” with The Wrong Definition.

If we add two numbers together that end in 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8, their sum must also end in 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8. Observe: , , … (and so on).∎

You might have wondered why I didn’t give “a number that ends in 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8” as the definition of an even number. I very well could have! But it turns out not to be very practical. Not only does the “proof” above illustrate that due to its length and tedious calculations, but we also could stage counterarguments to that second proof: why does only adding the last digits matter when adding two even numbers together? We would be tempted to say “It’s obvious”, but dig deeper than that. Why would we say that? Isn’t it because this is what we’ve always been taught about how to add two numbers? But what reason do we have to believe that? This level of skepticism is very healthy for a mathematician, and we will encourage that during this course as long as it is constructively aimed. (Some people may ask “why” about something without truly trying to learn or understand the answer given, and we will not entertain this in this class.)

This gives us an idea for a very important definition: the definition of proof:

Definition 0.1.3.

A proof is a deductive argument that a mathematical statement is true.

Notice the word “deductive” - this word carries a lot of weight in this definition. In the proof below we will deduce that the sum of two even numbers is even using only the definition:

Proof that the Sum of Two Even Numbers is Even.

Let and be two even numbers. We want to show that is an even number.

By definition, for some integer , and for some integer . (Sidenote: we are choosing a different label for the integer in this second number because the label is already taken. The label itself is not important - only the fact that is two times some other integer.)

Then .

Notice that is an integer, as the sum of two integers is an integer. Therefore is 2 times an integer, so by definition is an even number.∎

I encourage you to look through this proof a few times, as its structure reveals several things I will be looking for in your proofs.

-

1.

The proofs are easy to read. Every statement is written as a complete sentence. Notice my use of spacing where each idea is on its own line and how I give a brief explanation of how each step follows from the last.

-

2.

Every step contributes to the proof - I didn’t also say something like “the numbers or could be even or odd”, as that would not contribute anything to my proof.

-

3.

The proof has no meaningful counterargument - I started from a definition we agreed upon, and I ended with a definition we agreed upon, using only deductive techniques from beginning to end. (In this course we will learn several deductive techniques beyond the ones I used here.)

Some of you may not agree with me that I successfully addressed item 3: “why is the sum of two integers an integer?” you may ask. Truthfully, I must admit that there are some things that we must agree upon without proof for now. Sometimes it will not be clear what facts from your prior experience in mathematics you are ‘allowed’ to use. Unfortunately, addressing this issue is difficult and is something we will sort out along the way. In this case, basic facts about integers - such as the associative property, commutative property, the zero property, and so on - will be assumed to be true without proofs. These are all actually examples of axioms in our current understanding of the integers, and they are typically accepted without proof. These are discussed at the beginning of MATH 409, and you may find research into basic logic and mathematical axioms to be an interesting topic for your term paper… oh, did I mention there will be a term paper for this course?

0.1.6 Structure of This Course

Here is where we are going in this course:

-

1.

We will begin by discussing number theory as a vehicle for propositional logic (Chapters 1 & 2). At this stage we will be very formal about our proofs nearly to the point of tedium, explaining how each step follows from either a definition or a prior step we have made. We will use “know-show” tables and other tools to convince others that our proofs are correct.

-

2.

Our journey into propositional logic will continue into the Principle of Mathematical Induction (Chapter 3), which will help us understand how to prove facts about sequences and series especially (fun fact: we will prove that “the sum of the first positive integers is ).

-

3.

We will then introduce some basic set theory (Chapter 4). Currently all of modern mathematics is built upon our knowledge of sets, so in order to begin constructing useful definitions of mathematics we won’t be able to get started without understanding sets first.

-

4.

The first thing we will do with sets is build functions (Chapter 5). These mathematical objects are crucial in order to make math… well, function in nearly every application in the real world.

-

5.

We will end with discussing a bit more number theory (Chapter 6), some relations (Chapter 7) which set up the basis for applications like RSA cryptography, and if time permits we will discuss cardinality (Chapter 8), also known as “the exploration of infinity.” Perhaps “infinity” should be pluralized, as we would be exploring more than one infinity!

0.1.7 A Few Final Tips for Success

-

1.

One of my former students said they found success in a course very similar to this (MATH 409) by doing the following:

I think some of the things that helped me most were definitely making sure the homeworks got done in a timely manner and really trying my best to absorb that material as I came across it.

I kept an updated list of definitions/propositions/theorems/etc in order and went through their proofs the few days leading up to the exams so that they were fresh on my mind and make sure that I was able to do them on my own.

It also definitely helped to have a friend in that class to study with, as it’s nice to have different perspectives on how to approach problems!

-

2.

The courses that come after this one will take the content from this course for granted. In the case of MATH-409, there may be a one- or two-day review. But MATH-410/415/416/ 423/427/431/433/436/446/447/600+ will assume this content from the beginning. MATH-300 is the gateway to mathematical discovery - it is impossible to access mathematics past this without going through here. By the same token, once you’ve completed this course, the mathematics you can explore busts wide open.

I’m looking forward to joining you as we explore this mathematical world together!