3 Iterative Proof Techniques

3.1 Proof by Induction

Objectives:

-

•

Learn how to prove statements concerning infinite subsets of natural numbers

-

•

Apply induction to arguments of natural numbers

Example 3.1.1.

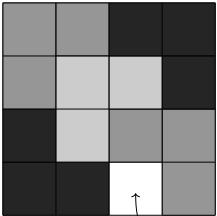

Below is a “proof without words” giving a closed form for the sum of the first natural numbers (credit to Art of Problem Solving for the image):

Put this “proof without words” into words. What is happening in this picture, and how could it be made into a formal proof of the equation above?

The natural numbers have a special structure that allows us to prove statements involving natural numbers in a different way: the induction proof. The dictionary defines induction as “The process of deriving general principles from particular facts or instances.” We have used another term for this in this class: “proof by example!” But we know that proofs by example are by no means welcome in the world of mathematics.

The process we take for these proofs, which we will still begrudgingly call induction proofs, would be better described as “iterative proofs”. An iteration is “a computational procedure in which a cycle of operations is repeated”.

So let be the universe of discourse and be a given predicate. If we would like to prove the statement , then here is how we could do it:

-

1.

Prove that is true.

-

2.

Prove that is true.

-

3.

Prove that is true.

-

-

608981813029.

Prove that is true.

-

Oh no! This looks awful! This is an infinite process that would take an infinite amount of time for anyone to solve. How would we have time to do anything else in this class?!

Perhaps we can save ourselves some time. Let’s rewrite this process slightly. To prove the statement , we could prove the following:

-

1.

Prove that is true. (Prove a base case is true.)

-

2.

Prove that, if is true, then is true (i.e., )

-

3.

Prove that, if is true, then is true (i.e., )…….

-

608981813029.

Prove that .

From Steps 2 onward we are proving that, if the statement from the previous step has been proven true, then the next step in the sequence should also be true. This is known as the domino effect: if one domino gets knocked down, then so does the next domino .

This is an interesting process. In terms of time to complete it is not any better, but it does set up a useful structure. Here comes the trick: we can shorten everything in steps 2 onward into one step: prove that the truth of the previous statement implies the truth of the statement with the next number in line.

-

1.

Prove that is true. (Base case)

-

2.

Prove that () is true. (Inductive step)

This yields the Principle of Mathematical Induction:

Theorem 3.1.2.

Let be a predicate over the natural numbers. Assume the following:

-

1.

the statement is true, and

-

2.

for all , if is true, then is true.

Then is true for all .

Example 3.1.3.

Watch the following Mr. Beast video and describe how it relates to induction. How many dominoes does Mr. Beast physically knock over? Why do all of the dominoes knock over?

Example 3.1.4.

Prove using induction that, for all ,

Example 3.1.5.

Fix a real number . Prove that, for all integers ,

(Note that we are no longer proving something is true on the natural numbers alone. What has to change?)

Example 3.1.6.

Prove the following statement: “For all integers , .”

Is this statement true when reframed as follows? “For all natural numbers , .” Prove or disprove.

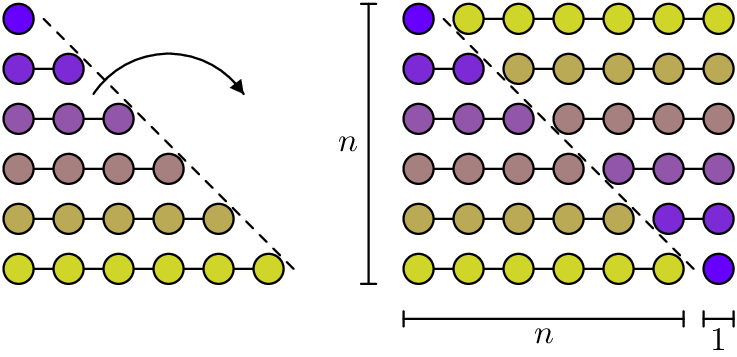

Example 3.1.7.

Consider a grid of squares that is squares wide by squares long, where . The number could be any value, so this could be a , , , … grid. One of the squares in the grid has been cut out - in the example below, say it’s the one with the arrow. You have a bunch of L-shaped “triominos” made up of 3 squares. Prove that you can perfectly cover this chessboard with the L-shaped triominos (with no overlap) for any , regardless of where the cut-out square is. (To clarify, once you’re given the board to cover, you can see the cut-out square, but you do not get to choose where the cut-out square is.)