7.3 Partitions

Objectives:

-

•

Discover a strong connection between equivalence relations and partitions

7.3.1 A New But Familiar Construction

Example 7.3.1.

A partition of is a (finite or infinite) collection of subsets. These subsets must satisfy the following conditions:

-

(i)

For each , (i.e., each subset is nonempty).

-

(ii)

For all , (i.e., the collection of sets is pairwise disjoint, meaning that no two sets share any elements).

-

(iii)

(i.e., every element of is contained within at least one subset).

Prove or disprove the following statements:

-

(a)

Blank space for you to write your work.

Let be the set of all odd integers and let be the set of all even integers. Then is a partition of .

-

(b)

Blank space for you to write your work.

Let . Then is a partition of .

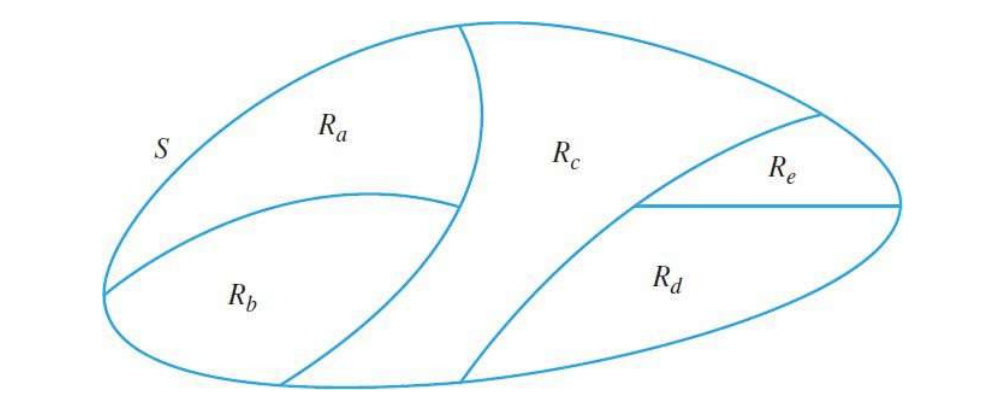

Let us revisit the diagram from the first Example of Section 7.2. Not all of our diagrams might look the same, but perhaps we might have a diagram like this:

In this diagram we noted that equivalence relations break up a set into regions. In the last example of Section 7.2 we saw that these regions satisfy a couple interesting properties. Do you see any connections between these properties and the definition of a partition?

Example 7.3.2.

Draw a diagram of a partition of . You may choose a partition from the previous example, or you may draw a different diagram. Justify that your diagram satisfies all three conditions of a partition.

7.3.2 Connecting Partitions and Equivalence Relations

Our goal in this section is to prove the statement you might be noticing from your diagram: equivalence relations and partitions are not so different from one another. Before we start proving this statement, let us investigate partitions a little further.

We begin with a formal definition, which should look very familiar to the definition we gave on the first page:

Definition 7.3.3.

Let be a set. A partition of is a (finite or infinite) collection of subsets. These subsets must satisfy the following conditions:

-

(i)

For each , (i.e., each subset is nonempty).

-

(ii)

For all , (i.e., the collection of sets is pairwise disjoint, meaning that no two sets share any elements).

-

(iii)

(i.e., every element of is contained within at least one subset).

We will call the subsets of blocks of the partition.

Example 7.3.4.

Find a partition of with exactly four blocks.

Example 7.3.5.

Find a partition of with infinitely many blocks.

Example 7.3.6.

Consider the relation on if . It is given that is an equivalence relation. Let be the equivalence class of under this equivalence relation. Show that the set of equivalence classes form a partition of .

Example 7.3.7.

Take your partition of with infinitely many blocks. Define a relation on such that if and are both in the same block of the partition. Show that is an equivalence relation.

In our previous two examples we saw a huge connection between our last two major concepts: “partition” and “equivalence relation”. We are now ready to prove a major connection between these two concepts:

Theorem 7.3.8.

Let be a set.

-

(a)

Blank space for you to write your work.

If is an equivalence relation on , then the set of equivalence classes form a partition on .

-

(b)

Blank space for you to write your work.

If is a partition of , then the relation defined by if there exists some such that is an equivalence relation.