5 Set Theory

5.4 Cartesian Products

5.4.1 Beginning Activity 1 (An Equation with Two Variables)

In Section 2.3, we introduced the concept of the truth set of an open sentence with one variable. This was defined to be the set of all elements in the universal set that can be substituted for the variable to make the open sentence a true statement.

In previous mathematics courses, we have also had experience with open sentences with two variables. For example, if we assume that and represent real numbers, then the equation

is an open sentence with two variables. An element of the truth set of this open sentence (also called a solution of the equation) is an ordered pair () of real numbers so that when is substituted for and is substituted for , the open sentence becomes a true statement (a true equation in this case). For example, we see that the ordered pair is in the truth set for this open sentence since

is a true statement. On the other hand, the ordered pair is not in the truth set for this open sentence since

is a false statement.

Important Note: The order of the two numbers in the ordered pair is very important. We are using the convention that the first number is to be substituted for and the second number is to be substituted for . With this convention, is a solution of the equation , but is not a solution of this equation.

-

1.

List six different elements of the truth set (often called the solution set) of the open sentence with two variables .

-

2.

From previous mathematics courses, we know that the graph of the equation is a straight line. Sketch the graph of the equation in the -coordinate plane. What does the graph of the equation show?

-

3.

Write a description of the solution set of the equation using set builder notation.

5.4.2 Beginning Activity 2 (The Cartesian Product of Two Sets)

In Activity 1, we worked with ordered pairs without providing a formal definition of an ordered pair. We instead relied on your previous work with ordered pairs, primarily from graphing equations with two variables. Following is a formal definition of an ordered pair.

Definition. Let and be sets. An ordered pair (with first element from and second element from ) is a single pair of objects, denoted by (), with and and an implied order. This means that for two ordered pairs to be equal, they must contain exactly the same objects in the same order. That is, if and , then

The objects in the ordered pair are called the coordinates of the ordered pair. In the ordered pair is the first coordinate and is the second coordinate.

We will now introduce a new set operation that gives a way of combining elements from two given sets to form ordered pairs. The basic idea is that we will create a set of ordered pairs.

Definition. If and are sets, then the Cartesian product, , of and is the set of all ordered pairs where and . We use the notation for the Cartesian product of and , and using set builder notation, we can write

We frequently read as " cross ." In the case where the two sets are the same, we will write for . That is,

Let and .

-

1.

Is the ordered pair () in the Cartesian product ? Explain.

-

2.

Is the ordered pair () in the Cartesian product ? Explain.

-

3.

Is the ordered pair in the Cartesian product ? Explain.

-

4.

Use the roster method to specify all the elements of . (Remember that the elements of will be ordered pairs.)

-

5.

Use the roster method to specify all of the elements of the set .

-

6.

List all the relationships between the sets in Part (1) that you observe.

5.4.3 The Cartesian Plane

In Beginning Activity 1, we sketched the graph of the equation in the -plane. This -plane, with which you are familiar, is a representation of the set or . This plane is called the Cartesian plane.

The basic idea is that each ordered pair of real numbers corresponds to a point in the plane, and each point in the plane corresponds to an ordered pair of real numbers. This geometric representation of is an extension of the geometric representation of as a straight line whose points correspond to real numbers.

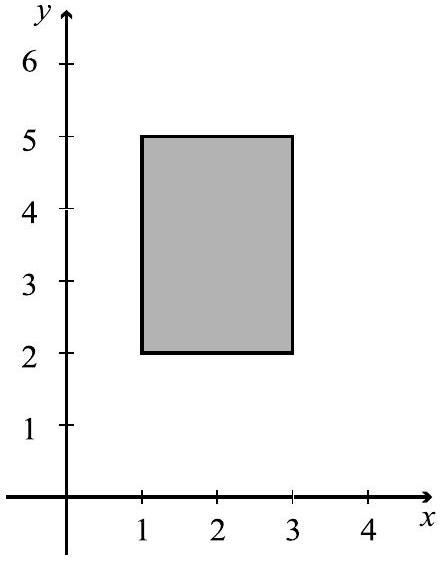

Since the Cartesian product corresponds to the Cartesian plane, the Cartesian product of two subsets of corresponds to a subset of the Cartesian plane. For example, if is the interval [ 1,3 ], and is the interval [ 2,5 ], then

A graph of the set can then be drawn in the Cartesian plane as shown in Figure 5.6.

This illustrates that the graph of a Cartesian product of two intervals of finite length in corresponds to the interior of a rectangle and possibly some or all of its

boundary. The solid line for the boundary in Figure 5.6 indicates that the boundary is included. In this case, the Cartesian product contained all of the boundary of the rectangle. When the graph does not contain a portion of the boundary, we usually draw that portion of the boundary with a dotted line.

Note: A Caution about Notation. The standard notation for an open interval in is the same as the notation for an ordered pair, which is an element of . We need to use the context in which the notation is used to determine which interpretation is intended. For example,

-

•

If we write , then we are using to represent an ordered pair of real numbers.

-

•

If we write , then we are interpreting as an open interval. We could write

The following progress check explores some of the same ideas explored in Progress Check 5.23 except that intervals of real numbers are used for the sets.

5.4.4 Progress Check 5.24 (Cartesian Products of Intervals)

We will use the following intervals that are subsets of .

-

1.

Draw a graph of each of the following subsets of the Cartesian plane and write each subset using set builder notation.

-

(a)

-

(b)

-

(c)

-

(d)

-

(e)

-

(f)

-

(g)

-

(h)

-

(i)

-

(j)

-

(a)

-

2.

List all the relationships between the sets in Part (1) that you observe.

One purpose of the work in Progress Checks 5.23 and 5.24 was to indicate the plausibility of many of the results contained in the next theorem.

Theorem 5.25. Let , and be sets. Then

-

1.

-

2.

-

3.

-

4.

-

5.

-

6.

-

7.

If , then .

-

8.

If , then .

We will not prove all these results; rather, we will prove Part (2) of Theorem 5.25 and leave some of the rest to the exercises. In constructing these proofs, we need to keep in mind that Cartesian products are sets, and so we follow many of the same principles to prove set relationships that were introduced in Sections 5.2 and 5.3.

The other thing to remember is that the elements of a Cartesian product are ordered pairs. So when we start a proof of a result such as Part (2) of Theorem 5.25, the primary goal is to prove that the two sets are equal. We will do this by proving that each one is a subset of the other one. So if we want to prove that , we can start by choosing an arbitrary element of . The goal is then to show that this element must be in . When we start by choosing an arbitrary element of , we could give that element a name. For example, we could start by letting

| (1) |

We can then use the definition of "ordered pair" to conclude that

| (2) |

In order to prove that , we must now show that the ordered pair from (1) is in . In order to do this, we can use the definition of set union and prove that

| (3) |

Since , we can prove (3) by proving that

| (4) |

If we look at the sentences in (2) and (4), it would seem that we are very close to proving that . Following is a proof of Part (2) of Theorem 5.25.

Theorem 5.25 (Part (2)). Let , and be sets. Then

Proof. Let , and be sets. We will prove that is equal to by proving that each set is a subset of the other set.

To prove that , we let . Then there exists and there exists such that . Since , we know that or .

In the case where , we have , where and . So in this case, , and hence . Similarly, in the case where , we have , where and . So in this case, and, hence, .

In both cases, . Hence, we may conclude that if is an element of , then , and this proves that

| (1) |

We must now prove that . So we let . Then or .

In the case where , we know that there exists and there exists such that . But since , we know that , and hence . Similarly, in the case where , we know that there exists and there exists such that . But because , we can conclude that and, hence, .

In both cases, . Hence, we may conclude that if , then , and this proves that

| (2) |

The relationshipsin (1) and (2) prove that .

Final Note. The definition of an ordered pair in Beginning Activity 2 may have seemed like a lengthy definition, but in some areas of mathematics, an even more formal and precise definition of "ordered pair" is needed. This definition is explored in Exercise (10).

5.4.5 Exercises for Section 5.4

-

1.

Let , and . Use the roster method to list all of the elements of each of the following sets:

-

(a)

-

(b)

-

(c)

-

(d)

-

(e)

-

(f)

-

(g)

-

(h)

-

(a)

-

2.

Sketch a graph of each of the following Cartesian products in the Cartesian plane.

-

(a)

-

(b)

-

(c)

-

(d)

-

(e)

-

(f)

-

(g)

-

(h)

-

(a)

-

3.

Prove Theorem 5.25, .

-

4.

Prove Theorem 5.25, Part (4): .

-

5.

Prove Theorem 5.25, Part (5): .

-

6.

Prove Theorem 5.25, Part (7): If , then .

-

7.

Let , and .

-

(a)

Explain why .

-

(b)

Explain why () × .

-

(a)

-

8.

Let and be nonempty sets. Prove that if and only if .

-

9.

Is the following proposition true or false? Justify your conclusion.

Let , and be sets with . If , then . Explain where the assumption that is needed.

5.4.6 Explorations and Activities

-

10.

(A Set Theoretic Definition of an Ordered Pair) In elementary mathematics, the notion of an ordered pair introduced at the beginning of this section will suffice. However, if we are interested in a formal development of the Cartesian product of two sets, we need a more precise definition of ordered pair. Following is one way to do this in terms of sets. This definition is credited to Kazimierz Kuratowski (1896-1980). Kuratowski was a famous Polish mathematician whose main work was in the areas of topology and set theory. He was appointed the Director of the Polish Academy of Sciences and served in that position for 19 years.

Let be an element of the set , and let be an element of the set . The ordered pair is defined to be the set . That is,

-

(a)

Explain how this definition allows us to distinguish between the ordered pairs and .

-

(b)

Let and be sets and let and . Use this definition of an ordered pair and the concept of set equality to prove that () if and only if and .

An ordered triple can be thought of as a single triple of objects, denoted by (), with an implied order. This means that in order for two ordered triples to be equal, they must contain exactly the same objects in the same order. That is, if and only if and .

-

(c)

Let , and be sets, and let , and . Write a set theoretic definition of the ordered triple similar to the set theoretic definition of "ordered pair."

-

(a)