6 Functions

6.3 Injections, Surjections, and Bijections

Functions are frequently used in mathematics to define and describe certain relationships between sets and other mathematical objects. In addition, functions can be used to impose certain mathematical structures on sets. In this section, we will study special types of functions that are used to describe these relationships that are called injections and surjections. Before defining these types of functions, we will revisit what the definition of a function tells us and explore certain functions with finite domains.

6.3.1 Beginning Activity 1 (Functions with Finite Domains)

Let and be sets. Given a function , we know the following:

-

•

For every . That is, every element of is an input for the function . This could also be stated as follows: For each , there exists a such that .

-

•

For a given , there is exactly one such that .

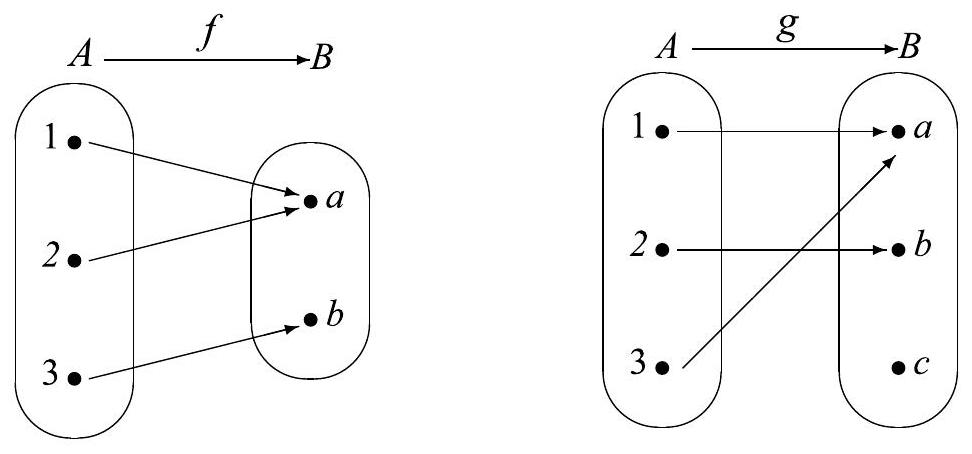

The definition of a function does not require that different inputs produce different outputs. That is, it is possible to have with and . The arrow diagram for the function in Figure 6.5 illustrates such a function.

Also, the definition of a function does not require that the range of the function must equal the codomain. The range is always a subset of the codomain, but these two sets are not required to be equal. That is, if , then it is possible to have a such that for all . The arrow diagram for the function in Figure 6.5 illustrates such a function.

Now let , and . Define

-

•

defined by .

-

•

defined by .

-

•

defined by .

-

1.

Which of these functions satisfy the following property for a function ?

For all , if , then .

-

2.

Which of these functions satisfy the following property for a function ?

For all , if , then .

-

3.

Determine the range of each of these functions.

-

4.

Which of these functions have their range equal to their codomain?

-

5.

Which of the these functions satisfy the following property for a function ?

For all in the codomain of , there exists an such that .

6.3.2 Beginning Activity 2 (Statements Involving Functions)

Let and be nonempty sets and let . In Beginning Activity 1, we determined whether or not certain functions satisfied some specified properties. These properties were written in the form of statements, and we will now examine these statements in more detail.

-

1.

Consider the following statement:

For all , if , then .

-

(a)

Write the contrapositive of this conditional statement.

-

(b)

Write the negation of this conditional statement.

-

(a)

-

2.

Now consider the statement:

For all , there exists an such that .

Write the negation of this statement. -

3.

Let be defined by , for all . Complete the following proofs of the following propositions about the function .

Proposition 1. For all , if , then .

Proof. We let , and we assume that and will prove that . Since , we know that(Now prove that in this situation, .)

Proposition 2. For all , there exists an such that .

Proof. We let . We will prove that there exists an such that by constructing such an in . In order for this to happen, we need .

(Now solve the equation for and then show that for this real number , .)

6.3.3 Injections

In previous sections and in Beginning Activity 1, we have seen examples of functions for which there exist different inputs that produce the same output. Using more formal notation, this means that there are functions for which there exist with and . The work in the beginning activities was intended to motivate the following definition.

Definition. Let be a function from the set to the set . The function is called an injection provided that

When is an injection, we also say that is a one-to-one function, or that is an injective function.

Notice that the condition that specifies that a function is an injection is given in the form of a conditional statement. As we shall see, in proofs, it is usually easier to use the contrapositive of this conditional statement. Although we did not define the term then, we have already written the contrapositive for the conditional statement in the definition of an injection in Part (1) of Beginning Activity 2. In that activity, we also wrote the negation of the definition of an injection. Following is a summary of this work giving the conditions for being an injection or not being an injection.

Let .

"The function is an injection" means that

-

•

For all , if , then ; or

-

•

For all , if , then . "The function is not an injection" means that

-

•

There exist such that and .

6.3.4 Progress Check 6.10 (Working with the Definition of an Injection)

Now that we have defined what it means for a function to be an injection, we can see that in Part (3) of Beginning Activity 2, we proved that the function is an injection, where for all . Use the definition (or its negation) to determine whether or not the following functions are injections.

-

1.

, where , and , and .

-

2.

, where , and , and .

-

3.

defined by for all

-

4.

defined by for all

-

5.

and defined by for all .

6.3.5 Surjections

In previous sections and in Beginning Activity 1, we have seen that there exist functions for which range . This means that every element of is an output of the function for some input from the set . Using quantifiers, this means that for every , there exists an such that . One of the objectives of the beginning activities was to motivate the following definition.

Definition. Let be a function from the set to the set . The function is called a surjection provided that the range of equals the codomain of . This means that

for every , there exists an such that .

When is a surjection, we also say that is an onto function or that maps onto . We also say that is a surjective function.

One of the conditions that specifies that a function is a surjection is given in the form of a universally quantified statement, which is the primary statement used in proving a function is (or is not) a surjection. Although we did not define the term then, we have already written the negation for the statement defining a surjection in Part (2) of Beginning Activity 2. We now summarize the conditions for being a surjection or not being a surjection.

Let .

"The function is a surjection" means that

-

•

; or

-

•

For every , there exists an such that .

"The function is not a surjection" means that -

•

range ; or

-

•

There exists a such that for all .

One other important type of function is when a function is both an injection and surjection. This type of function is called a bijection.

Definition. A bijection is a function that is both an injection and a surjection. If the function is a bijection, we also say that is one-to-one and onto and that is a bijective function.

6.3.6 Progress Check 6.11 (Working with the Definition of a Surjection)

Now that we have defined what it means for a function to be a surjection, we can see that in Part (3) of Beginning Activity 2, we proved that the function is a surjection, where for all . Determine whether or not the following functions are surjections.

-

1.

, where , and , and .

-

2.

defined by for all .

-

3.

defined by for all .

-

4.

defined by for all .

6.3.7 The Importance of the Domain and Codomain

The functions in the next two examples will illustrate why the domain and the codomain of a function are just as important as the rule defining the outputs of a function when we need to determine if the function is a surjection.

An Important Lesson. In Examples 6.12 and 6.13, the same mathematical formula was used to determine the outputs for the functions. However, one function was not a surjection and the other one was a surjection. This illustrates the important fact that whether a function is surjective depends not only on the formula that defines the output of the function but also on the domain and codomain of the function.

The next example will show that whether or not a function is an injection also depends on the domain of the function.

6.3.8 Example 6.14 (A Function that Is an Injection but Is Not a Surjection)

Let . Define by . (Notice that this is the same formula used in Examples 6.12 and 6.13.) Following is a table of values for some inputs for the function .

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 5 |

| 3 | 10 |

| 4 | 17 |

| 5 | 26 |

Notice that the codomain is , and the table of values suggests that some natural numbers are not outputs of this function. So it appears that the function is not a surjection.

To prove that is not a surjection, pick an element of that does not appear to be in the range. We will use 3, and we will use a proof by contradiction to prove that there is no in the domain () such that . So we assume that there exists an with . Then

But this is not possible since . Therefore, there is no with . This means that for every . Therefore, 3 is not in the range of , and hence is not a surjection.

The table of values suggests that different inputs produce different outputs, and hence that is an injection. To prove that is an injection, assume that

(the domain) with . Then

Since , we know that and . So the preceding equation implies that . Hence, is an injection.

An Important Lesson. The functions in the three preceding examples all used the same formula to determine the outputs. The functions in Examples 6.12 and 6.13 are not injections but the function in Example 6.14 is an injection. This illustrates the important fact that whether a function is injective not only depends on the formula that defines the output of the function but also on the domain of the function.

6.3.9 Progress Check 6.15 (The Importance of the Domain and Codomain)

Let . Define

Determine if each of these functions is an injection or a surjection. Justify your conclusions. Note: Before writing proofs, it might be helpful to draw the graph of . A reasonable graph can be obtained using and . Please keep in mind that the graph does not prove any conclusion, but may help us arrive at the correct conclusions, which will still need proof.

6.3.10 Working with a Function of Two Variables

It takes time and practice to become efficient at working with the formal definitions of injection and surjection. As we have seen, all parts of a function are important (the domain, the codomain, and the rule for determining outputs). This is especially true for functions of two variables.

For example, we define by

Notice that both the domain and the codomain of this function are the set . Thus, the inputs and the outputs of this function are ordered pairs of real numbers. For example,

To explore whether or not is an injection, we assume that , , and . This means that

Since this equation is an equality of ordered pairs, we see that

By adding the corresponding sides of the two equations in this system, we obtain and hence, . Substituting into either equation in the system give us . Since and , we conclude that

Hence, we have shown that if , then . Therefore, is an injection.

Now, to determine if is a surjection, we let , where is considered to be an arbitrary element of the codomain of the function . Can we find an ordered pair such that ? Working backward, we see that in order to do this, we need

That is, we need

Solving this system for and yields

Since , we can conclude that and and hence that .

We now need to verify that for these values of and , we get . So

This proves that for all , there exists such that . Hence, the function is a surjection. Since is both an injection and a surjection, it is a bijection.

6.3.11 Progress Check 6.16 (A Function of Two Variables)

Let be defined by , for all .

Note: Be careful! One major difference between this function and the previous example is that for the function , the codomain is , not . It is a good idea to begin by computing several outputs for several inputs (and remember that the inputs are ordered pairs).

-

1.

Notice that the ordered pair . That is, is in the domain of . Also notice that . Is it possible to find another ordered pair such that ?

-

2.

Let . Then and so . Now determine .

-

3.

Is the function an injection? Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

6.3.12 Exercises 6.3

-

1.

-

(a)

Draw an arrow diagram that represents a function that is an injection but is not a surjection.

-

(b)

Draw an arrow diagram that represents a function that is an injection and is a surjection.

-

(c)

Draw an arrow diagram that represents a function that is not an injection and is not a surjection.

-

(d)

Draw an arrow diagram that represents a function that is not an injection but is a surjection.

-

(e)

Draw an arrow diagram that represents a function that is not a bijection.

-

(a)

-

2.

We know and . For each of the following functions, determine if the function is an injection and determine if the function is a surjection. Justify all conclusions.

-

(a)

by , for all

-

(b)

by , for all

-

(c)

by , for all

-

(a)

-

3.

For each of the following functions, determine if the function is an injection and determine if the function is a surjection. Justify all conclusions.

-

(a)

defined by , for all .

-

(b)

defined by , for all .

-

(c)

defined by , for all .

-

(d)

defined by , for all .

-

(e)

defined by , for all .

-

(f)

defined by , for all .

Note: .

-

(g)

defined by , for all , where .

-

(h)

defined by , for all .

-

(i)

defined by , for all .

-

(a)

-

4.

For each of the following functions, determine if the function is a bijection. Justify all conclusions.

-

(a)

defined by , for all .

-

(b)

defined by , for all .

-

(c)

defined by , for all .

-

(d)

defined by , for all .

-

(a)

-

5.

Let , where for each is the sum of the distinct natural number divisors of . This is the sum of the divisors function that was introduced in Beginning Activity 2 from Section 6.1. Is an injection? Is a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

6.

Let , where is the number of natural number divisors of . This is the number of divisors function introduced in Exercise (6) from Section 6.1.. Is the function an injection? Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

7.

In Beginning Activity 2 from Section 6.1., we introduced the birthday function. Is the birthday function an injection? Is it a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

8.

-

(a)

Let be defined by . Is the function an injection? Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

(b)

Let be defined by . Is the function an injection? Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

(a)

-

9.

-

(a)

Let be defined by . Is the function an injection? Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

(b)

Let be defined by . Is the function an injection? Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

(a)

-

10.

Let be the function defined by , for all . Is the function an injection? Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

11.

Let be the function defined by , for all . Is the function an injection? Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

12.

Let be a nonempty set. The identity function on the set , denoted by , is the function defined by for every in . Is an injection? Is a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

13.

Let and be two nonempty sets. Define

for every . This is the first projection function introduced in Exercise (5) in Section 6.2..

-

(a)

Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusion.

-

(b)

If , is the function an injection? Justify your conclusion.

-

(c)

Under what condition(s) is the function not an injection? Make a conjecture and prove it.

-

(a)

-

14.

Define as follows: For each ,

Is the function an injection? Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

Suggestions. Start by calculating several outputs for the function before you attempt to write a proof. In exploring whether or not the function is an injection, it might be a good idea to use cases based on whether the inputs are even or odd. In exploring whether is a surjection, consider using cases based on whether the output is positive or less than or equal to zero.

-

15.

Let be the set of all real functions that are continuous on the closed interval . Define the function as follows: For each ,

Is the function an injection? Is it a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

16.

Let , and . Define as follows:

-

(a)

Is the function an injection? Justify your conclusion.

-

(b)

Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusion.

-

(a)

-

17.

Evaluation of proofs. See the instructions for Exercise (19) from Section 3.1.

-

(a)

Proposition. The function defined by is an injection.

Proof. For each and in , if , then

We will use systems of equations to prove that and .

Since , we see that

So . Therefore, we have proved that the function is an injection.

-

(b)

Proposition. The function defined by is a surjection.

Proof. We need to find an ordered pair such that for each in . That is, we need , or

Treating these two equations as a system of equations and solving for and , we find that

Hence, and are real numbers, , and

Therefore, we have proved that for every , there exists an such that . This proves that the function is a surjection.

-

(a)

6.3.13 Explorations and Activities

-

18.

Piecewise Defined Functions. We often say that a function is a piecewise defined function if it has different rules for determining the output for different parts of its domain. For example, we can define a function by giving a rule for calculating when and giving a rule for calculating when as follows:

-

(a)

Sketch a graph of the function . Is the function an injection? Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

For each of the following functions, determine if the function is an injection and determine if the function is a surjection. Justify all conclusions.

-

(b)

by

-

(c)

by

-

(a)

-

19.

Functions Whose Domain is . Let represent the set of all 2 by 2 matrices over .

-

(a)

Define det: by

This is the determinant function introduced in Exercise (9) from Section 6.2.. Is the determinant function an injection? Is the determinant function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

(b)

Define tran: by

This is the transpose function introduced in Exercise (10) from Section 6.2.. Is the transpose function an injection? Is the transpose function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

(c)

Define by

Is the function an injection? Is the function a surjection? Justify your conclusions.

-

(a)