6 Functions

6.4 Composition of Functions

6.4.1 Beginning Activity 1 (Constructing a New Function)

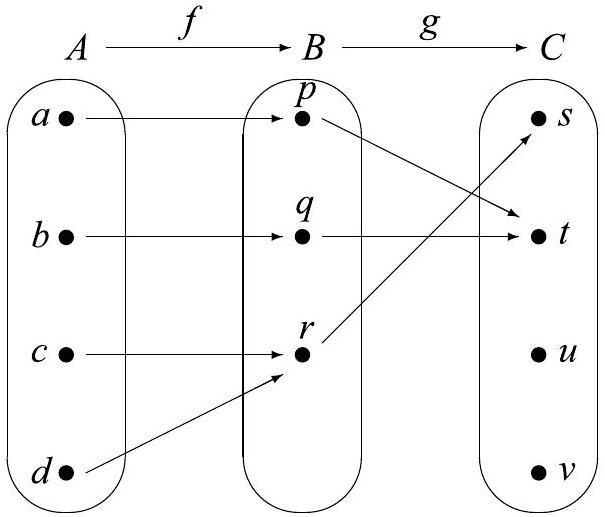

Let , and . The arrow diagram in Figure 6.6 shows two functions: and . Notice that if , then . Since , we can apply the function to , and we obtain , which is an element of .

Using this process, determine , and . Then explain how we can use this information to define a function from to .

6.4.2 Beginning Activity 2 (Verbal Descriptions of Functions)

The outputs of most real functions we have studied in previous mathematics courses have been determined by mathematical expressions. In many cases, it is possible to use these expressions to give step-by-step verbal descriptions of how to compute the outputs. For example, if

we could describe how to compute the outputs as follows:

| Step | Verbal Description | Symbolic Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Choose an input. | |

| 2 | Multiply by 3. | |

| 3 | Add 2. | |

| 4 | Cube the result. |

Complete step-by-step verbal descriptions for each of the following functions.

-

1.

by , for each .

-

2.

by , for each .

-

3.

by , for each .

-

4.

by , for each .

-

5.

by , for each .

6.4.3 Composition of Functions

There are several ways to combine two existing functions to create a new function. For example, in calculus, we learned how to form the product and quotient of two functions and then how to use the product rule to determine the derivative of a product of two functions and the quotient rule to determine the derivative of the quotient of two functions.

The chain rule in calculus was used to determine the derivative of the composition of two functions, and in this section, we will focus only on the composition of two functions. We will then consider some results about the compositions of injections and surjections.

The basic idea of function composition is that when possible, the output of a function is used as the input of a function . This can be referred to as " followed by " and is called the composition of and . In previous mathematics courses, we used this idea to determine a formula for the composition of two real functions.

For example, if

then we can compute as follows:

In this case, , the output of the function , was used as the input for the function . We now give the formal definition of the composition of two functions.

Definition. Let , and be nonempty sets, and let and be functions. The composition of and is the function defined by

for all . We often refer to the function as a composite function.

It is helpful to think of the composite function as " followed by ." We then refer to as the inner function and as the outer function.

6.4.4 Composition and Arrow Diagrams

The concept of the composition of two functions can be illustrated with arrow diagrams when the domain and codomain of the functions are small, finite sets. Although the term "composition" was not used then, this was done in Beginning Activity 1, and another example is given here.

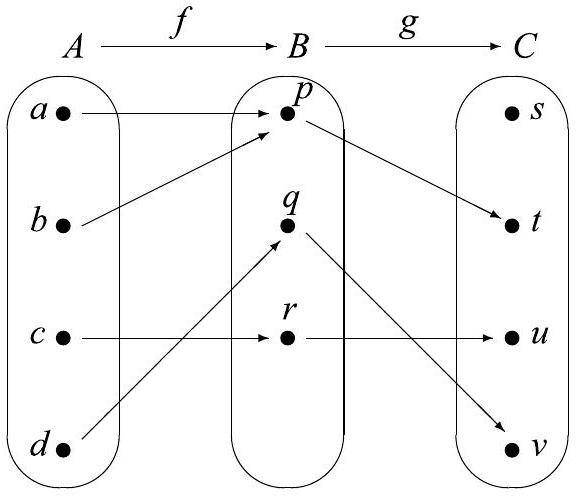

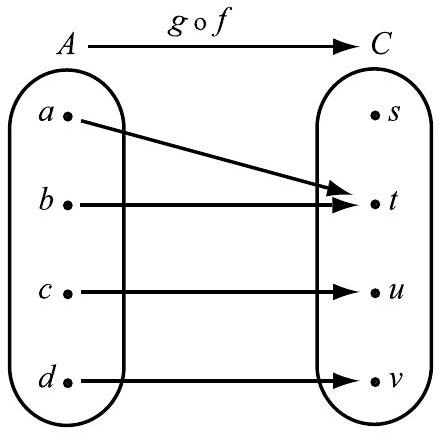

Let , and . The arrow diagram in Figure 6.7 shows two functions: and .

If we follow the arrows from the set to the set , we will use the outputs of as inputs of , and get the arrow diagram from to shown in Figure 6.8. This diagram represents the composition of followed by .

6.4.5 Progress Check 6.17 (The Composition of Two Functions)

Let and . Define the functions and as follows:

Create arrow diagrams for the functions , and .

6.4.6 Decomposing Functions

We use the chain rule in calculus to find the derivative of a composite function. The first step in the process is to recognize a given function as a composite function. This can be done in many ways, but the work in Beginning Activity 2 can be used to decompose a function in a way that works well with the chain rule. The use of the terms "inner function" and "outer function" can also be helpful. The idea is that we use the last step in the process to represent the outer function, and the steps prior to that to represent the inner function. So for the function,

the last step in the verbal description table was to cube the result. This means that we will use the function (the cubing function) as the outer function and will use the prior steps as the inner function. We will denote the inner function by . So we let by and by . Then

We see that and, hence, we have "decomposed" the function . It should be noted that there are other ways to write the function as a composition of two functions, but the way just described is the one that works well with the chain rule. In this case, the chain rule gives

6.4.7 Progress Check 6.18 (Decomposing Functions)

Write each of the following functions as the composition of two functions.

-

1.

by

-

2.

by

-

3.

by

-

4.

by

6.4.8 Theorems about Composite Functions

If and , then we can form the composite function . In Section 6.3, we learned about injections and surjections. We now explore what type of function will be if the functions and are injections (or surjections).

6.4.9 Progress Check 6.19 (Compositions of Injections and Surjections)

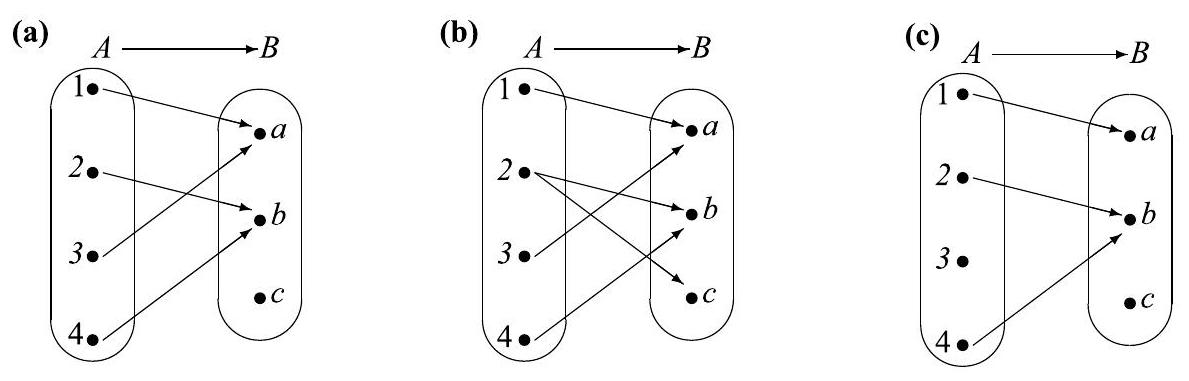

Although other representations of functions can be used, it will be helpful to use arrow diagrams to represent the functions in this progress check. We will use the following sets:

-

1.

Draw an arrow diagram for a function that is an injection and an arrow diagram for a function that is an injection. In this case, is the composite function an injection? Explain.

-

2.

Draw an arrow diagram for a function that is a surjection and an arrow diagram for a function that is a surjection. In this case, is the composite function a surjection? Explain.

-

3.

Draw an arrow diagram for a function that is a bijection and an arrow diagram for a function that is a bijection. In this case, is the composite function bijection? Explain.

In Progress Check 6.19, we explored some properties of composite functions related to injections, surjections, and bijections. The following theorem contains

results that these explorations were intended to illustrate. Some of the proofs will be included in the exercises.

Theorem 6.20. Let , and be nonempty sets and assume that and .

-

1.

If and are both injections, then (): is an injection.

-

2.

If and are both surjections, then is a surjection.

-

3.

If and are both bijections, then is a bijection.

The proof of Part (1) is Exercise (6). Part (3) is a direct consequence of the first two parts. We will discuss a process for constructing a proof of Part (2). Using the forward-backward process, we first look at the conclusion of the conditional statement in Part (2). The goal is to prove that is a surjection. Since , this is equivalent to proving that

For all , there exists an such that .

Since this statement in the backward process uses a universal quantifier, we will use the choose-an-element method and choose an arbitrary element in the set . The goal now is to find an such that .

Now we can look at the hypotheses. In particular, we are assuming that both and are surjections. Since we have chosen , and is a surjection, we know that

there exists a such that .

Now, and is a surjection. Hence

there exists an such that .

If we now compute , we will see that

We can now write the proof as follows:

Proof of Theorem 6.20, Part (2). Let , and be nonempty sets and assume that and are both surjections. We will prove that is a surjection.

Let be an arbitrary element of . We will prove there exists an such that . Since is a surjection, we conclude that

there exists a such that .

Now, and is a surjection. Hence

there exists an such that .

We now see that

We have now shown that for every , there exists an such that , and this proves that is a surjection.

Theorem 6.20 shows us that if and are both special types of functions, then the composition of followed by is also that type of function. The next question is, "If the composition of followed by is an injection (or surjection), can we make any conclusions about or ?" A partial answer to this question is provided in Theorem 6.21. This theorem will be investigated and proved in the Explorations and Activities for this section. See Exercise (10).

Theorem 6.21. Let , and be nonempty sets and assume that and .

-

1.

If is an injection, then is an injection.

-

2.

If is a surjection, then is a surjection.

6.4.10 Exercises 6.4

-

1.

In our definition of the composition of two functions, and , we required that the domain of be equal to the codomain of . However, it is sometimes possible to form the composite function even though . For example, let

-

(a)

Is it possible to determine for all ? Explain.

-

(b)

In general, let and . Find a condition on the domain of (other than ) that results in a meaningful definition of the composite function .

-

(a)

-

2.

Let be defined by and be defined by . Determine formulas for the composite functions and . Is the function equal to the function ? Explain. What does this tell you about the operation of composition of functions?

-

3.

Following are formulas for certain real functions. Write each of these real functions as the composition of two functions. That is, decompose each of the functions.

-

(a)

-

(b)

-

(c)

-

(d)

-

(a)

-

4.

The identity function on a set , denoted by , is defined as follows: by for each . Let .

-

(a)

For each , determine and use this to prove that .

-

(b)

Prove that .

-

(a)

-

5.

-

(a)

Let be defined by , let be defined by , and let be defined by .

Determine formulas for and . Does this prove that for these particular functions? Explain.

-

(b)

Now let , and be sets and let , and . Prove that . That is, prove that function composition is an associative operation.

-

(a)

-

6.

Prove Part (1) of Theorem 6.20. Let , and be nonempty sets and let and . If and are both injections, then is an injection.

-

7.

For each of the following, give an example of functions and that satisfy the stated conditions, or explain why no such example exists.

-

(a)

The function is a surjection, but the function is not a surjection.

-

(b)

The function is an injection, but the function is not an injection.

-

(c)

The function is a surjection, but the function is not a surjection.

-

(d)

The function is an injection, but the function is not an injection.

-

(e)

The function is not a surjection, but the function is a surjection.

-

(f)

The function is not an injection, but the function is an injection.

-

(g)

The function is not a surjection, but the function is a surjection.

-

(h)

The function is not an injection, but the function is an injection.

-

(a)

-

8.

Let be a nonempty set and let . For each , define a function recursively as follows: and for each , . For example, and .

-

(a)

Let by for each . For each and for each , determine a formula for and use induction to prove that your formula is correct.

-

(b)

Let and let by for each . For each and for each , determine a formula for and use induction to prove that your formula is correct.

-

(c)

Now let be a nonempty set and let . Use induction to prove that for each . (Note: You will need to use the result in Exercise (5).)

-

(a)

6.4.11 Explorations and Activities

-

9.

Exploring Composite Functions. Let , and be nonempty sets and let and . For this activity, it may be useful to draw your arrow diagrams in a triangular arrangement as follows:

It might be helpful to consider examples where the sets are small. Try constructing examples where the set has 2 elements, the set has 3 elements, and the set has 2 elements.

-

(a)

Is it possible to construct an example where is an injection, is an injection, but is not an injection? Either construct such an example or explain why it is not possible.

-

(b)

Is it possible to construct an example where is an injection, is an injection, but is not an injection? Either construct such an example or explain why it is not possible.

-

(c)

Is it possible to construct an example where is a surjection, is a surjection, but is not a surjection? Either construct such an example or explain why it is not possible.

-

(d)

Is it possible to construct an example where is surjection, is a surjection, but is not a surjection? Either construct such an example or explain why it is not possible.

-

(a)

-

10.

The Proof of Theorem 6.21. Use the ideas from Exercise (9) to prove Theorem 6.21. Let , and be nonempty sets and let and .

-

(a)

If is an injection, then is an injection.

-

(b)

If is a surjection, then is a surjection.

Hint: For part (a), start by asking, "What do we have to do to prove that is an injection?" Start with a similar question for part (b).

-

(a)