6 Functions

6.5 Inverse Functions

For this section, we will use the concept of Cartesian product of two sets and , denoted by , which is the set of all ordered pairs () where and . That is,

See Beginning Activity 2 in Section 5.4 for a more thorough discussion of this concept.

6.5.1 Beginning Activity 1 (Functions and Sets of Ordered Pairs)

When we graph a real function, we plot ordered pairs in the Cartesian plane where the first coordinate is the input of the function and the second coordinate is the output of the function. For example, if , then every point on the graph of is an ordered pair of real numbers where . This shows how we can generate ordered pairs from a function. It happens that we can do this with any function. For example, let

Define the function by

We can convert each of these to an ordered pair in by using the input as the first coordinate and the output as the second coordinate. For example, is converted to is converted to , and is converted to . So we can think of this function as a set of ordered pairs, which is a subset of , and write

Note: Since is the name of the function, it is customary to use as the name for the set of ordered pairs.

-

1.

Let and let . Define the function by , and . Write the function as a set of ordered pairs in .

For another example, if we have a real function, such as by , then we can think of as the following infinite subset of :

We can also write this as .

-

2.

Let be defined by , for all . Use set builder notation to write the function as a set of ordered pairs, and then use the roster method to write the function as a set of ordered pairs.

So any function can be thought of as a set of ordered pairs that is a subset of . This subset is

On the other hand, if we started with , and

then we could think of as a function from to with , and . The idea is to use the first coordinate of each ordered pair as the input, and the second coordinate as the output. However, not every subset of can be used to define a function from to . This is explored in the following questions.

-

3.

Let . Could this set of ordered pairs be used to define a function from to ? Explain.

-

4.

Let . Could this set of ordered pairs be used to define a function from to ? Explain.

-

5.

Let . Could this set of ordered pairs be used to define a function from to ? Explain.

6.5.2 Beginning Activity 2 (A Composition of Two Specific Functions)

Let and let .

-

1.

Construct an example of a function that is a bijection. Draw an arrow diagram for this function.

-

2.

On your arrow diagram, draw an arrow from each element of back to its corresponding element in . Explain why this defines a function from to A.

-

3.

If the name of the function in Part (2) is , so that , what are , , and

-

4.

Construct a table of values for each of the functions and . What do you observe about these tables of values?

6.5.3 The Ordered Pair Representation of a Function

In Beginning Activity 1, we observed that if we have a function , we can generate a set of ordered pairs that is a subset of as follows:

However, we also learned that some sets of ordered pairs cannot be used to define a function. We now wish to explore under what conditions a set of ordered pairs can be used to define a function. Starting with a function , since , we know that

| (1) |

Specifically, we use . This says that every element of can be used as an input. In addition, to be a function, each input can produce only one output. In terms of ordered pairs, this means that there will never be two ordered pairs and () in the function where , and . We can formulate this as a conditional statement as follows:

| (2) |

This also means that if we start with a subset of that satisfies conditions (1) and (2), then we can consider to be a function from to by using whenever is in . This proves the following theorem.

Theorem 6.22. Let and be nonempty sets and let be a subset of that satisfies the following two properties:

-

•

For every , there exists such that ; and

-

•

For every and every , if and , then .

If we use whenever , then is a function from to .

A Note about Theorem 6.22. The first condition in Theorem 6.22 means that every element of is an input, and the second condition ensures that every input has exactly one output. Many texts will use Theorem 6.22 as the definition of a function. Many mathematicians believe that this ordered pair representation of a function is the most rigorous definition of a function. It allows us to use set theory to work with and compare functions. For example, equality of functions becomes a question of equality of sets. Therefore, many textbooks will use the ordered pair representation of a function as the definition of a function.

6.5.4 Progress Check 6.23 (Sets of Ordered Pairs that Are Not Functions)

Let and let . Explain why each of the following subsets of cannot be used to define a function from to .

-

1.

.

-

2.

.

6.5.5 The Inverse of a Function

In previous mathematics courses, we learned that the exponential function (with base ) and the natural logarithm function are inverses of each other. This was often expressed as follows:

For each with and for each , if and only if .

Notice that this means that is the input and is the output for the natural logarithm function if and only if is the input and is the output for the exponential function. In essence, the inverse function (in this case, the exponential function) reverses the action of the original function (in this case, the natural logarithm function). In terms of ordered pairs (input-output pairs), this means that if is an ordered pair for a function, then is an ordered pair for its inverse. This idea of reversing the roles of the first and second coordinates is the basis for our definition of the inverse of a function.

Definition. Let be a function. The inverse of , denoted by , is the set of ordered pairs . That is,

If we use the ordered pair representation for , we could also write

Notice that this definition does not state that is a function. It is simply a subset of . After we study the material in Chapter 7, we will say that this means that is a relation from to . This fact, however, is not important to us now. We are mainly interested in the following question:

6.5.6 Progress Check 6.24 (Exploring the Inverse of a Function)

Let , and . Define

| by | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| by | ||||

| by |

-

1.

Draw an arrow diagram for each function.

-

2.

Determine the inverse of each function as a set of ordered pairs.

-

3.

-

(a)

Is a function from to ? Explain.

-

(b)

Is a function from to ? Explain.

-

(c)

Is a function from to ? Explain.

-

(d)

Draw an arrow diagram for each inverse from Part (3) that is a function. Use your existing arrow diagram from Part (1) to draw this arrow diagram.

-

(e)

Make a conjecture about what conditions on a function will ensure that its inverse is a function from to .

-

(a)

6.5.7 Conditions for an Inverse Function

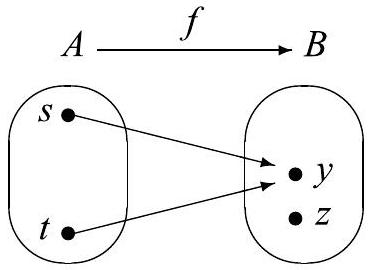

We will now consider a general argument suggested by the explorations in Progress Check 6.24. By definition, if is a function, then is a subset of . However, may or may not be a function from to . For example, suppose that with and . This is represented in Figure 6.9.

In this case, if we try to reverse the arrows, we will not get a function from to . This is because and with . Consequently, is not a function. This suggests that when is not an injection, then is not a function.

Also, if is not a surjection, then there exists a such that for all , as in the diagram in Figure 6.9. In other words, there is no ordered pair in with as the second coordinate. This means that there would be no ordered pair in with as a first coordinate. Consequently, cannot be a function from to .

This motivates the statement in Theorem 6.25. In the proof of this theorem, we will frequently change back and forth from the input-output representation of a function and the ordered pair representation of a function. The idea is that if is a function, then for and ,

When we use the ordered pair representation of a function, we will also use the ordered pair representation of its inverse. In this case, we know that

Theorem 6.25. Let and be nonempty sets and let . The inverse of is a function from to if and only if is a bijection.

Proof. Let and be nonempty sets and let . We will first assume

that is a bijection and prove that is a function from to . To do this, we will show that satisfies the two conditions of Theorem 6.22.

We first choose . Since the function is a surjection, there exists an such that . This implies that and hence that . Thus, each element of is the first coordinate of an ordered pair in , and hence satisfies the first condition of Theorem 6.22.

To prove that satisfies the second condition of Theorem 6.22, we must show that each element of is the first coordinate of exactly one ordered pair in . So let and assume that

This means that and . We can then conclude that

But this means that . Since is a bijection, it is an injection, and we can conclude that . This proves that is the first element of only one ordered pair in . Consequently, we have proved that satisfies both conditions of Theorem 6.22 and hence that is a function from to .

We now assume that is a function from to and prove that is a bijection. First, to prove that is an injection, we assume that and that . We wish to show that . If we let , we can conclude that

But this means that

Since we have assumed that is a function, we can conclude that . Hence, is an injection.

Now to prove that is a surjection, we choose and will show that there exists an such that . Since is a function, must be the first coordinate of some ordered pair in . Consequently, there exists an such that

Now this implies that and hence that . This proves that is a surjection. Since we have also proved that is an injection, we conclude that is a bijection.

6.5.8 Inverse Function Notation

In the situation where is a bijection and is a function from to , we can write . In this case, we frequently say that is an invertible function, and we usually do not use the ordered pair representation for either or . Instead of writing , we write , and instead of writing , we write . Using the fact that if and only if , we can now write if and only if . We summarize this in Theorem 6.26.

Theorem 6.26. Let and be nonempty sets and let be a bijection. Then is a function, and for every and ,

6.5.9 Example 6.27 (Inverse Function Notation)

For an example of the use of the notation in Theorem 6.26, let . Define

Notice that is the codomain of . We can then say that both and are bijections. Consequently, the inverses of these functions are also functions. In fact,

For each function (and its inverse), we can write the result of Theorem 6.26 as follows:

| Theorem 6.26 | Translates to: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

|

|

6.5.10 Theorems about Inverse Functions

The next two results in this section are two important theorems about inverse functions. The first is actually a corollary of Theorem 6.26.

Corollary 6.28. Let and be nonempty sets and let be a bijection. Then

-

1.

For every in .

-

2.

For every in .

Proof. Let and be nonempty sets and assume that is a bijection. So let and let . By Theorem 6.26, we can conclude that . Therefore,

Hence, for each .

The proof that for each in is Exercise (4).

6.5.11 Example 6.27 (continued)

For the cubing function and the cube root function, we have seen that

Notice that

-

•

If we substitute into the equation , we obtain .

-

•

If we substitute into the equation , we obtain .

This is an illustration of Corollary 6.28. We can see this by using defined by and defined by . Then and . So for each ,

Similarly, the equation for each can be obtained from the fact that for each .

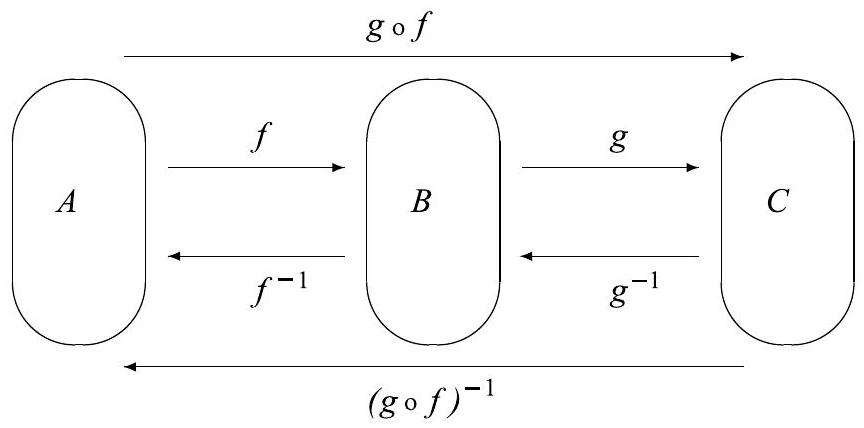

We will now consider the case where and are both bijections. In this case, and . Figure 6.10 can be used to illustrate this situation.

By Theorem 6.20, is also a bijection. Hence, by Theorem 6.25, is a function and, in fact, . Notice that we can also form the composition of followed by to get . Figure 6.10 helps illustrate the result of the next theorem.

Theorem 6.29. Let and be bijections. Then is a bijection and .

Proof. Let and be bijections. Then and . Hence, . Also, by Theorem 6.20, is a bijection, and hence . We will now prove that for each .

Let . Since the function is a surjection, there exists a such that

| (1) |

Also, since is a surjection, there exists an such that

| (2) |

Now these two equations can be written in terms of the respective inverse functions as

| (3) | ||||

| (4) |

Using equations (3) and (4), we see that

| (5) |

Using equations (1) and (2) again, we see that . However, in terms of the inverse function, this means that

| (6) |

Comparing equations (5) and (6), we have shown that for all , . This proves that .

6.5.12 Exercises 6.5

-

1.

Let and .

-

(a)

Construct an example of a function that is not a bijection. Write the inverse of this function as a set of ordered pairs. Is the inverse of a function? Explain. If so, draw an arrow diagram for and .

-

(b)

Construct an example of a function that is a bijection. Write the inverse of this function as a set of ordered pairs. Is the inverse of a function? Explain. If so, draw an arrow diagram for and .

-

(a)

-

2.

Let . Define by defining to be the following set of ordered pairs.

-

(a)

Draw an arrow diagram to represent the function . Is the function a bijection?

-

(b)

Write the inverse of as a set of ordered pairs. Is a function? Explain.

-

(c)

Draw an arrow diagram for using the arrow diagram from Exercise (2a).

-

(d)

Compute and for each in . What theorem does this illustrate?

-

(a)

-

3.

Inverse functions can be used to help solve certain equations. The idea is to use an inverse function to undo the function.

-

(a)

Since the cube root function and the cubing function are inverses of each other, we can often use the cube root function to help solve an equation involving a cube. For example, the main step in solving the equation

is to take the cube root of each side of the equation. This gives

Explain how this step in solving the equation is a use of Corollary 6.28.

-

(b)

A main step in solving the equation is to take the natural logarithm of both sides of this equation. Explain how this step is a use of Corollary 6.28, and then solve the resulting equation to obtain a solution for in terms of the natural logarithm function.

-

(c)

How are the methods of solving the equations in Exercise (3a) and Exercise (3b) similar?

-

(a)

-

4.

Prove Part (2) of Corollary 6.28. Let and be nonempty sets and let be a bijection. Then for every in .

-

5.

In Progress Check 6.6, we defined the identity function on a set. The identity function on the set , denoted by , is the function defined by for every in . Explain how Corollary 6.28 can be stated using the concept of equality of functions and the identity functions on the sets and .

-

6.

Let and . Let and be the identity functions on the sets and , respectively. Prove each of the following:

-

(a)

If , then is an injection.

-

(b)

If , then is a surjection.

-

(c)

If and , then and are bijections and .

-

(a)

-

7.

-

(a)

Define by . Is the inverse of a function? Justify your conclusion.

-

(b)

Let . Define by . Is the inverse of a function? Justify your conclusion.

-

(a)

-

8.

-

(a)

Let be defined by . Explain why the inverse of is not a function.

-

(b)

Let . Define by . Explain why this squaring function (with a restricted domain and codomain) is a bijection.

-

(c)

Explain how to define the square root function as the inverse of the function in Exercise (8b).

-

(d)

True or false: for all such that .

-

(e)

True or false: for all .

-

(a)

-

9.

Prove the following:

If is a bijection, then is also a bijection.

-

10.

For each natural number , let be a set, and for each natural number , let .

For example, , and so on.

Use mathematical induction to prove that for each natural number with , if are all bijections, then is a bijection andNote: This is an extension of Theorem 6.29. In fact, Theorem 6.29 is the basis step of this proof for .

-

11.

-

(a)

Define by for all . Explain why the inverse of the function is not a function.

-

(b)

Let and let . Define by for all . Explain why the inverse of the function is a function and find a formula for , where .

-

(a)

-

12.

Let .

-

(a)

Define by for all . Write the inverse of as a set of ordered pairs and explain why is not a function.

-

(b)

Define by for all . Write the inverse of as a set of ordered pairs and explain why is a function.

-

(c)

Is it possible to write a formula for , where ? The answer to this question depends on whether or not it is possible to define a cube root of elements of . Recall that for a real number , we define the cube root of to be the real number such that . That is,

Using this idea, is it possible to define the cube root of each number in ? If so, what are , and ?

-

(d)

Now answer the question posed at the beginning of Part (c). If possible, determine a formula for where .

-

(a)

6.5.13 Explorations and Activities

-

13.

Constructing an Inverse Function. If is a bijection, then we know that its inverse is a function. If we are given a formula for the function , it may be desirable to determine a formula for the function . This can sometimes be done, while at other times it is very difficult or even impossible.

Let be defined by . A graph of this function would suggest that this function is a bijection.

-

(a)

Prove that the function is an injection and a surjection.

Let . One way to prove that is a surjection is to set and solve for . If this can be done, then we would know that there exists an such that . For the function , we are using for the

input and for the output. By solving for in terms of , we are attempting to write a formula where is the input and is the output. This formula represents the inverse function. -

(b)

Solve the equation for . Use this to write a formula for , where .

-

(c)

Use the result of Part (13b) to verify that for each and for each .

Now let . Define by .

-

(d)

Set and solve for in terms of .

-

(e)

Use your work in Exercise (13d) to define a function .

-

(f)

For each , determine and for each , determine .

-

(g)

Use Exercise (6) to explain why .

-

(a)

-

14.

The Inverse Sine Function. We have seen that in order to obtain an inverse function, it is sometimes necessary to restrict the domain (or the codomain) of a function.

-

(a)

Let be defined by . Explain why the inverse of the function is not a function. (A graph may be helpful.)

Notice that if we use the ordered pair representation, then the sine function can be represented as

If we denote the inverse of the sine function by , then

Part (14a) proves that is not a function. However, in previous mathematics courses, we frequently used the "inverse sine function." This is not really the inverse of the sine function as defined in Part (14a) but, rather, it is the inverse of the sine function restricted to the domain .

-

(b)

Explain why the function defined by is a bijection.

The inverse of the function in Part (14b) is itself a function and is called the inverse sine function (or sometimes the arcsine function).

-

(c)

What is the domain of the inverse sine function? What are the range and codomain of the inverse sine function?

Let us now use to represent the restricted sine function in Part (14b). Therefore, can be used to represent the inverse sine function. Observe that

-

(d)

Using this notation, explain why

-

(a)